Training programs with at least some participants together in one location required field office staff support to help facilitate in-person. Although local staff is knowledgeable about the subject matter, a key challenge is to ensure that they can also impart that knowledge in a classroom setting to the required standard.

This is the third in a series about how GHSC-PSM adapted its programming to the new COVID-19 environment. Check out the first, second and fourth installments.

GHSC-PSM strengthens public health supply chains through more than 30 country offices using a systemic approach to training and professionalization of the workforce, putting countries on a path to sustainability.

Travel restrictions from COVID-19 prevented international travel beginning in April 2020. Travel restrictions within partner countries varied depending on the severity of the pandemic, with cities, local regions and entire countries going into lockdown at different times. These two factors led to two types of environments for international training programs, with an international training advisor facilitating with:

- Some or all participants on-site in a meeting facility, or

- All participants remotely

Each type of program required differing approaches and brought distinct challenges.

In the case of a one-week training in Liberia on the logistics management information system, the international advisor recruited four potential co-facilitators from the country office. He then conducted a thorough training of trainers to select the two best co-facilitators, requiring many more preparation hours than an in-person program.

During the actual training program – which was the training of trainers – the two field office co-facilitators led portions of the agenda at which they excelled during the evaluation period. Linked by an internet connection, the international advisor led the remaining sessions, with presentations projected at the front of the room. The 20 participants and three facilitators also used a WhatsApp group to communicate electronically. At the end of each day, the team of three facilitators met virtually to review and discuss areas for improvement and plans for the next day.

One challenge with this type of training is to ensure that participants are committed to learning and applying knowledge and skills. This can be especially challenging to assess by remote support, and field office co-facilitators helped monitor participation. A competency evaluation at the end of each session graded participants; participants also had to lead a mini training session to demonstrate their teaching ability. Only those who passed received a certificate of training to train others. Those who didn't pass received only a certificate of participation.

At times, COVID lockdowns forced all training participants to attend from home or other remote locations. In addition to the challenges of facilitating this type of training, many participants had limited or no internet connectivity, especially in residential or rural areas.

An example from Rwanda illustrates how GHSC-PSM managed a program with the Bureau des Formations Médicales Agréées du Rwanda (BUFMAR) – a private, faith-based medical supply store – to build leadership skills of senior managers and medical directors in selected BUFMAR-affiliated hospitals. Following an in-person training immediately pre-COVID, some 20 participants developed 'capstone' projects in which they examined vital challenges in their work and developed plans of action to address those challenges. At the culmination of three months of planning and implementation, the participants reported their progress at a completely remote, two-day event.

Throughout the three months of activity, Rwanda experienced periods of lockdown in which participants remained at home. GHSC-PSM employed every available mode of communication to continue to connect with and provide feedback.

Participants had no funding for at-home internet access. To allow them to continue to develop – and later present – their capstone projects, GHSC-PSM provided them cellular data airtime to connect to the internet from their laptop computers. The international advisors provided feedback and coaching primarily through email and sent text messages to alert trainees when to check their email.

With this type of remote training and coaching, personal relations were crucial for ensuring program success. In addition to the international advisor, four field co-facilitators—including a professor from the Regional Centre of Excellence (RCE)—supported the program. When possible, they made bi-weekly, on-the-job visits or remote discussions to review progress and serve as mentors. The international advisor dedicated significant time and effort to build relationships and develop a personal bond by asking about and understanding their competing priorities, issues with family and childcare, and more. This level of understanding helped the advisor know who was struggling, focus attention on them, and find ways to keep them on track. The personal relationships meant that emails, text, advice and more would be less likely to be ignored during a very challenging time. At times, due to competing priorities, discussions took place at odd hours and on weekends.

For the two-day final presentations, Microsoft Teams served as the meeting platform, and facilitators used WhatsApp to manage time during presentations. Despite time management efforts, the two planned three-hour sessions extended to six hours due to various factors, including connectivity issues and an abundance of interest and questions from other participants.

Although the program was initially designed to include several in-person sessions, the program succeeded in its goals, and all participants completed the program.

In addition to internationally led programs, GHSC-PSM's country programs also lead workforce development programs and developed ways to continue to engage them despite challenges related to COVID-19.

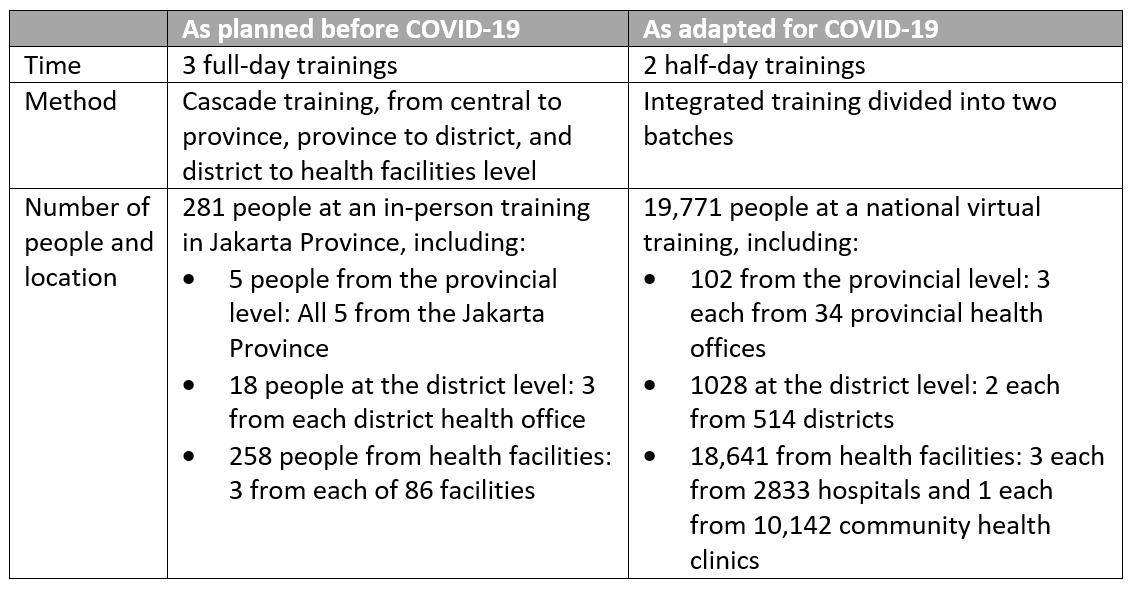

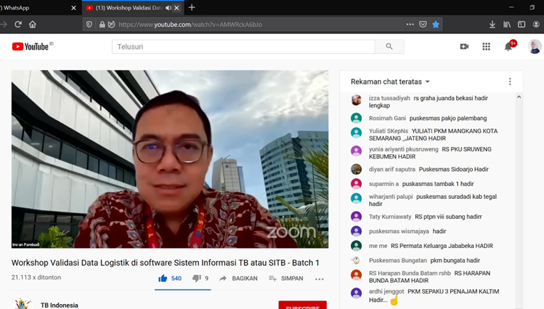

GHSC-PSM’s switch from in-person to online training allowed the project to reach 70 times more people than would have been possible through a planned in-person training. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, GHSC-PSM, the National Tuberculosis Program and TB-STAR (a USAID-funded program) transitioned from an in-person to a virtual workshop on the TB Information System (SITB) logistics data validation for 12,900 health facilities in 514 districts and 34 provinces. The workshop aimed to improve the quality and accuracy of logistics management data for the national TB program by training participants on logistics modules in SITB, including ordering, distribution, and dispensing. The workshop also encouraged health facilities to input logistics data into SITB and reinforced the role of district and provincial health offices to validate and use SITB data to manage the program.

The event provided two options for attendance, with 1,000 attending by Zoom and 2,700 by YouTube (Clip 1 and Clip 2). Both Zoom and YouTube participants could later review the recording of the YouTube workshop to help them implement what they learned. As of February 23, 2021, 439 out of 514 (85%) districts have used the logistic module since the training.

The table below shows how the project adapted the program in the context of COVID.

Understanding that audience engagement can be a key challenge with on-line training, the project implemented several interactive tools to create interest, including quizzes, awards, testimonies, and satisfaction surveys. Because YouTube is less interactive as a training platform, the project concluded that Zoom is a preferred platform and, for such a large number of participants, would plan to assign attendees to breakout rooms in the future and assign more facilitators.

Since the live program, more than 26,000 people have viewed a recording on YouTube and posted more than 100 questions.

Since the live event, more than 26,000 people have viewed a recording of Indonesia’s training on YouTube.

In Mali, GHSC-PSM launched an innovative e-learning platform for OSPSANTE—a USAID-funded LMIS tool essential to the MOH's logistics data management system—with the first video: "Data entry in OSPSANTE." The platform helps overcome travel restrictions because of COVID-19, providing online training for Local Health Information System (SLIS) officers. The original training program had planned to provide in-person training at dozens of locations and for hundreds of SLIS officers. The primary channel for disseminating the tutorial is now through implementing partners’ WhatsApp groups. The tutorials will be available at any time for users to quickly and easily learn their role in keeping data up to date in OSPSANTE. In addition to anticipated cost reduction for training, the new program can be updated more quickly with new information, eliminates travel time for training, is less disruptive to workflow than in-person training, and is available to an unlimited number of participants. It also more effectively addresses the issue of high turnover of staff in the Bamako region and elsewhere. OSPSANTE facilitates collection and data analysis for HIV/AIDS, malaria, FP/RH, and MNCH commodities.

Although getting approval from government partners for the training took five months, the program has proved to be popular, in part because moving to online training has eliminated costs related to travel and in-person training and provided convenience for those to be trained. Based on the success of the tutorial, government partners requested further tutorials for DHIS2 entry, data analysis, and OSPSANTE-DHIS2 interoperability.

An OPSANTE user in Mali. Photo: GHSC-PSM.

Adapting technical support to the context of the COVID-19 pandemic required flexibility, creativity and new and old technologies. Doing so also required bearing in mind that colleagues were facing many challenges, including increased responsibilities for teaching and caring for children and the stress of the pandemic itself.

The move to remote and recorded training may signal a long-term trend in some areas. Online and recorded training provides the opportunity for training to happen at any time the participant chooses and reduces travel. Yet internet connectivity remains a critical challenge, especially in remote, residential and rural areas. Although some may assume that remote support is typically less expensive than in-person programs, the budgetary implications are mixed. While remote support can save money in travel, room rental, catering and more, it can require additional costs in preparation time; purchase or rental of video and sound equipment; design, recording, updating training videos; and other related needs. In addition, financial considerations are not the only factor to consider. Some activities are best done in-person, and many people find value in the informal communication and relationship building that happens during unstructured time. Strong relationships help get things done.

The use of new technologies for workforce development and training has increased the capacity—and confidence—of in-country technical teams to lead technical support sessions, whereas in the past they were mostly participants and observers while international experts led.

Just as working from home – at least or two days a week – may become a permanent part of many professional workplaces, technical support for public health supply chain management will likely maintain the most desired adaptations from the COVID-19 era. At a minimum, lessons learned can be quickly applied during future crises, including natural disasters, political upheaval and public health emergencies.